Imagine if when you launched a gaming app on your smartphone, the device could automatically morph into the shape of a console. Then, if you received a text message and needed to respond, it could transform itself back into a phone.

Researchers at the University of Bristol, in the United Kingdom, have designed a device that could one day do just that. It’s called Cubimorph, and it’s a small, modular device that can change into different shapes, depending on the desired function or even who is holding it. Its designers say the technology could pave the way to more adaptable handheld gadgets.

The project was recently presented at the IEEE Robotics and Automation Society’s largest conference, the International Conference on Robotics and Automation, which was held May 16-21 in Stockholm, Sweden.

Man + machine

There has been growing interest in how humans and computers interact, especially with how modular devices like the Cubimorph could help bridge the gap between what machines and humans hands can do.

“I’m very interested in how, as humans, we manipulate things,” said Anne Roudaut, a lecturer in the Department of Computer Science at the University of Bristol and lead researcher of the Cubimorph project. “When we see a bottle of water on the table, we know exactly how we can use our hand to grasp it, or if you see a door handle, you know exactly what kind of movement you need to do to actually open the door.”

Roudaut said she wants to introduce this range of functionality to machines, so that a device can automatically manipulate itself for optimum and easy use by the person holding it.

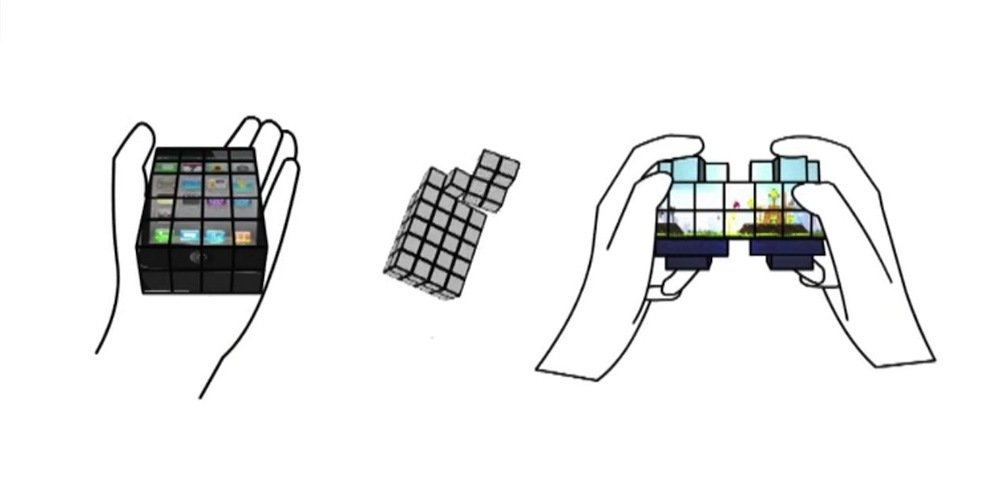

The modular device could change into different shapes, depending on the desired function. For instance, it could morph into the shape of a gaming console when a user launches a gaming app.

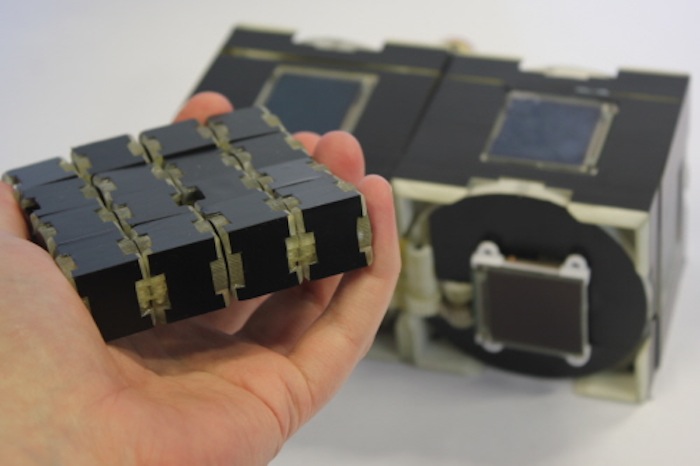

Credit: Roudaut et al/University of Bristol

Looking a bit like a Rubik’s Cube, the Cubimorph is made from a string of connected smaller cubes, with each surface covered in a tiny touch screen. The cubes are on hinges that allow movement across any of the edges, controlled by two motors.

A detailed algorithm is used to transform the device seamlessly from one shape into another by mapping out the path the Cubimorph takes to change from shape to shape. The user doesn’t have to think about the process, and it’s designed so that no parts of the device collide with each other, and there’s no chance the moving pieces snap shut on the user’s fingers, the researchers said.

“I think there [are] actually plenty of applications. The game industry is one of the — maybe the most — obvious one,” Roudaut told Live Science. “You’re playing a game on your phone, and the shape changes to resemble more a game controller, so you would grasp it in a better way.”

This technology could also have educational benefits, the researchers said. For instance, it could be used to visualize a map or different terrains.

“One very interesting aspect would be to adapt the shape to different morphology,” Roudaut said. “For example, [for] kids or elderly people, or people who have some impairment, we can just change the shape so that it fits what people can do with their hands.”

Overcoming obstacles

But while the researchers can already envision many different uses for the Cubimorph, there were challenges to overcome in finding the correct algorithm.

“There are some algorithms that are physically transforming a chain of modules into one shape to another, and we thought, ‘Great, we can use it,'” Roudaut said. “The problem is that these algorithms go from one shape, to a straight line and then fall back into another shape.”

The issue here is that if a future, complicated version of the Cubimorph consisted of 1,000 or more squares, it wouldn’t be practical for it to morph into a long line and then back into another shape, Roudaut said. This would be especially true if the user was walking down the street or commuting on a busy train, she said. Taking this into consideration when designing the technology is what makes things really complicated, she added.

The future vision for Cubimorph is for everybody to create whatever shape they want, Roudaut said. If in 15 or 20 years a big company like Samsung, Nokia or Apple made a device capable of sophisticated transformation, then any programmer or user could customize the gadget however they wanted.

Roudaut said that ideally this would be similar to how game design works now. That is, people can download applications and then anybody can create a game, she said. “I think it’s the future,” she said.

Roudaut said this device could be on the market as soon as 10 years from now, but the researchers are looking for helpful insights from other robotics teams.

“We decided to present this paper at the robotic conference because we thought this project had quite a lot [to gain] from people from the robotics sector,” she said. “There is a lot of work to make this a reality, but it’s really exciting, because there are a lot of new challenges and new questions that have not been investigated so far.”